I have been thinking back to the post-1918 pandemic and the impact that it and other widespread infectious diseases at the time had on design development. It has been dawning on designers that the materials and finishes we specify for interiors from now on may need to be inherently hygienic or at least easy to clean. Does this mean the end of opulent interiors with layers and layers of materials such as salvaged timbers with all their imperfect nobbles and knots, of cosy over-stuffed sofas, of luxurious carpets with a thick pile, of dust-harbouring wall hangings, of heavy and unnecessary curtains… I think a little look back at the atmosphere in which the ‘heroic’ phase of modernism came about, and the breath of fresh air that the new ‘luxurious austerity’ offered, might be interesting.

It isn’t that widely understood that modernism as we know it came about as a response to an urgent need to provide clean and healthy buildings for society. More than just a design aesthetic born out of a response to new technology, the rhetoric of the modern movement was full of references to health, hygiene and social improvement. Although the 1918 influenza pandemic doesn’t tend to be mentioned as a reason for it as much as tuberculosis does, it’s clear from our current perspective that this very likely played a part in changing perspectives around design and its relationship to public health.

Dirt and Decoration

Adolf Loos had compared ornament with crime in his 1908 essay because it seemed to him to be superfluous and gratuitous, adding no real value to a lot of the objects it adorned. This way of thinking was part of a design reform current which we could trace back to William Morris (‘have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful’, 1882) as a reaction to mechanised manufacturing methods and the exploitation of workers, when badly designed factory-made goods were being churned out and brightened up with tacked on decoration. This was wasteful in terms of materials, time and money. Furthermore, however, ornament came to be thought of as unhygienic, as mouldings on walls, ceilings and joinery harboured dust and germs (germ theory was developed in the 1850s and urban sanitation was encouraged through proper drainage systems and the provision of public baths; cleanliness became a preoccupation of the bourgeoisie). Loos’s architecture seemed shockingly austere at the time but, like Louis Sullivan who wrote that ‘form ever follows function’ he used ornament in a considered and holistic way and employed quality materials which were inherently beautiful.

Glamour in austerity

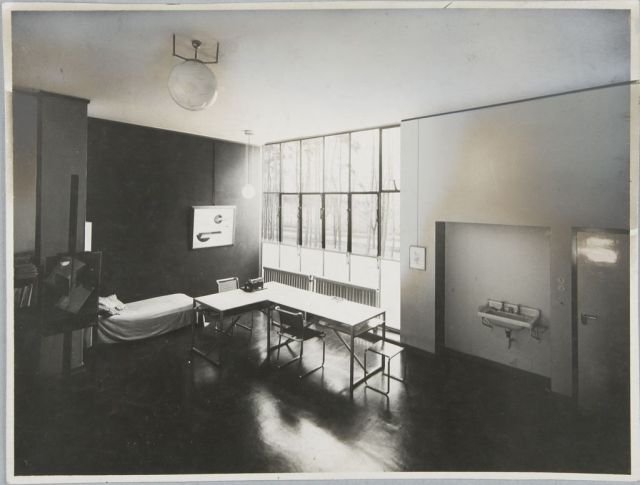

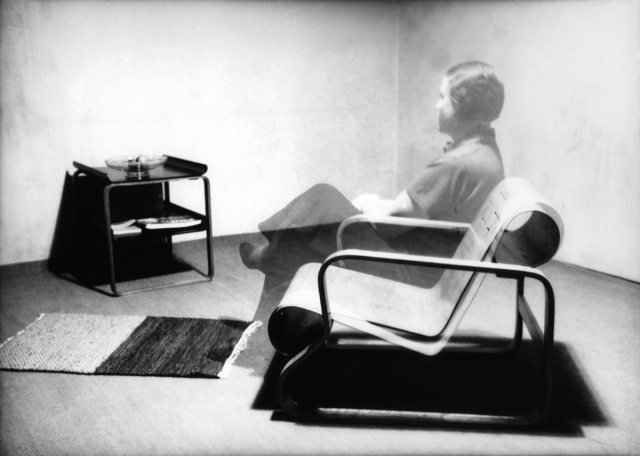

In the 1920s the innovative use of materials such as chromed steel, glass, rubber and terrazzo transformed interiors, not to mention the use of a plain, smooth rendered ‘skin’ to exteriors which was symbolic of health and cleanliness. This is sometimes referred to as a ‘sanatorium aesthetic’, of which Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium became an iconic example, and it was echoed in every building typology that the ‘moderns’ produced, regardless of their purpose. The conceptual thread that seemed to tie all the building typologies together was the preoccupation with health. The construction of ‘health factories’, which could include the private house (cue white cuboid villas with balconies and sun terraces), swimming baths or lidos, educational buildings and hospitals obviously – ANY building type had an excuse to be designed on healthy lines. The architect took the role of public health practitioner upon him/herself in the inter war years. Healthy architecture was lean and efficient, like the ideal promoted for the human body. By the 1930s this healthy aesthetic was seen as appropriate but also modern and quite glamorous. There were jokes about interiors looking like operating theatres and furniture like hospital trollies; but once glamorous hotels, the homes of the wealthy and Hollywood set designs took on these attributes suddenly austerity became luxurious.

One contemporary writer (for Architectural Review in 1932) described this new approach as being ‘as refreshing after the ever recurring stodge, as is spring salad after a protracted diet of boiled beef and all its ghastly accessories’. What I am now wondering is, will a ‘luxurious austerity’ become our ‘new normal’, at least for the time being? And then will we see a surge in creativity in which new smart materials will be developed and employed in bolder and better ways?

Bauhaus Masters’ Housing by Walter Gropius, 1925-26 (photo by Lucia Moholy, featured here:https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/photo-credit-negatives-bauhaus/)

Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Chair designed for the sanatorium, 1931-32. The collaged or double exposure effect teases us about the ergonomics of the chair, showing it as a functional support for the body, almost like an exoskeleton.

*’Luxurious Austerity’ is a phrase used in Paul Overy’s Light Air and Openness, Modern Architecture Between the Wars (Thames & Hudson, 2007).

Note: Unauthorised use and or duplication of this material without express and written permission from the site’s author and or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to the author with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.